Evidence of a coordinated network amplifying inauthentic narratives in the 2020 US election

On 15 September 2020, The Washington Post published an article by Isaac Stanley-Becker titled “Pro-Trump youth group enlists teens in secretive campaign likened to a ‘troll farm,’ prompting rebuke by Facebook and Twitter.” The article reported on a network of accounts run by teenagers in Phoenix, who were coordinated and paid by an affiliate of conservative youth organization Turning Point USA. These accounts posted identical messages amplifying political narratives, including false claims about COVID-19 and electoral fraud. The same campaign was run on Twitter and Facebook, and both platforms suspended some of the accounts following queries from Stanley-Becker. The report was based in part on a preliminary analysis we conducted at the request of The Post. In this brief we provide further details about our analysis.

Our Observatory on Social Media at Indiana University has been studying social media manipulation and online misinformation for over ten years. We uncovered the first known instances of astroturf campaigns, social bots, and fake news websites during the 2010 US midterm election, long before these phenomena became widely known in 2016. We develop public, state-of-the-art network and data science methods and tools, such as Botometer, Hoaxy, and BotSlayer, to help researchers, journalists, and civil society organizations study coordinated inauthentic campaigns. So when Stanley-Becker contacted us about accounts posting identical political content on Twitter, Pik-Mai Hui and Fil Menczer were happy to apply our analytical framework to map out what was going on.

We started from a set of accounts provided to us and followed a so-called “snowball” procedure, iteratively adding accounts that recently posted content (excluding retweets) identical to at least two accounts in the current set. That led to the discovery of 35 Twitter accounts (two of which had already been banned) that had posted 4,401 tweets with identical content. Most of the accounts posting this content had been created recently and had few followers (see charts).

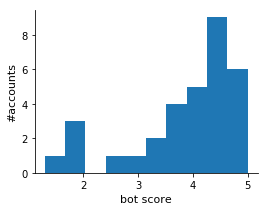

Our analysis found characteristic behaviors suggesting some use of automation. Many of the accounts were given high scores by the Botometer model, which is trained on various classes of social bots, including “astroturf” accounts (see chart). The Post reported that at least some of the accounts were being operated by humans. It is of course impossible to know who or what is behind an account with absolute certainty. Software can be used by an actor to control multiple inauthentic accounts even though their actions are manually triggered.

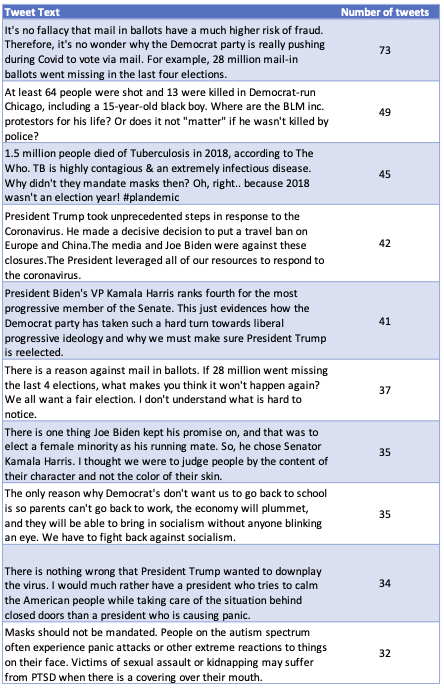

We found 467 messages posted in at least two tweets, 188 posted by at least two accounts. Content was reportedly being copied and pasted from a shared source with minor variations. Identical messages, including those amplifying false narratives, appeared in dozens of tweets (see top ten in table).

We also found that 95% of the tweets were replies to posts from media organizations (see top 25 in table). This is a targeting strategy documented in our previous research about bot-amplification of low-credibility information during the 2016 election.

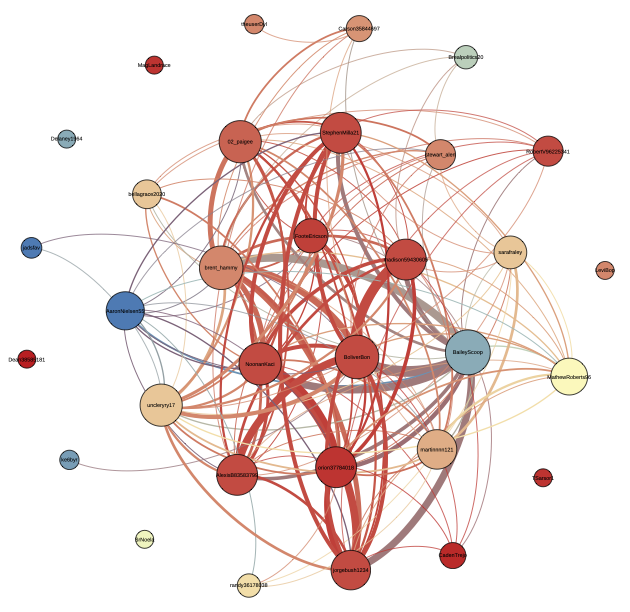

Finally, we mapped the coordination network. (see figure at top). Nodes represent accounts and edges represent the similarity between them, measured as the content overlap — number of common identical political messages. Each message is only counted once, even if posted many times. Node color is based on bot score (red is higher) and node size on number of accounts with overlapping messages.

We are making the data collected for our analysis publicly available (DOI:10.5281/zenodo.4050225) for anyone who wishes to carry out further investigations.